When your organization is faced with investigating a security incident, whether that’s something as simple as a phishing campaign or more complex like a determined human adversary, time is of the essence. Collecting and analyzing data are two critical things that need to be performed to quickly get an understanding of the initial scope and impact of the incident. There are several variables around both collecting and analyzing data that can affect the speed at which you might be able to respond. While the method or process of collecting data (or even the availability of relevant incident data) is unique to each organization, the analysis of that data is something that can be sped up to reduce the time it takes to make tactical and strategic decisions.

In this blog, we’ll show you how the Microsoft Detection and Response Team (DART) uses the Kusto Query Language (KQL) to quickly analyze data during incident response investigations.

Why KQL?

Kusto allows for various ingestion methods and various data formats. Data can be structured to best suit your use case in a table using data mappings, and when use cases arise that call for additional data (e.g., third party logs) you can import on the fly via Azure Data Explorer using One-Click Ingestion. In order to query the data, we use and recommend Azure Data Explorer.

Data Sources

When Microsoft DART is on the prowl for threat actors in customer environments, we leverage Microsoft Defender for Endpoint and Microsoft Defender for Identity as two primary data sources. Of course, we do not limit our scope to just Microsoft security products. Every organization has its own third-party logs that are vital to the investigation, which typically includes firewalls, VPNs, proxy logs, etc. We take all of this data and ingest it into a Kusto cluster and database to leverage KQL for fast and efficient analysis.

Analyzing data to scope the attack impact

The ultimate outcome of data analysis is to be able to make decisions based on what the data is telling us. Specifically with incident response investigations, data analysis plays a vital role in being able to scope the impact of the attack, identify new leads to hunt down, and provide insight into how to contain the threat. Leaders within the organization need the results of this analysis to quickly understand what they’re facing and to make decisions based on factual data. In the all-too-common cases of a ransomware attack, you may be faced with the decision to minimize the threat by shutting down network access. Do you have enough information to warrant a shutdown of the entire network or are only certain sites affected? Having analysis completed quickly can help in turn allow for faster decision-making.

What used to take hours with reviewing logs in Excel or even SQL databases, can now be done in seconds with KQL. This is possible in part due to the power of KQL which comes from native functions that help quickly parse and/or convert data to something more meaningful to an analyst. Some example functionality this provides is being able to decode Base64 data, parse URLs, and even parse command line arguments. Additionally, for any parsing or working with data that requires a bit more complexity than native querying, KQL does have plug-ins that can extend its use by leveraging Python and R.

Built-in Functions useful for Incident Response

Not unlike other large-data or database query languages, KQL allows you to:

- filter your data (with ‘where’ clauses);

- present your data (with either ‘project’ or ‘render’ clauses); and

- aggregate your data (with ‘summarize’ clauses).

The real power of KQL, though, comes from its various native functions that can be used to parse or transform data on the fly, including (and certainly not limited to) :

- base64_decode_tostring()

- gzip_decompress_from_base64_string()

- ipv4_is_private()

- parse_command_line()

- parse_json()

- parse_path()

- parse_url()

- parse_urlquery()

- parse_user_agent()

- parse_xml()

- url_decode()

- zlib_decompress_from_base64_string()

These functions are named in a self-explanatory way, but let’s look at a couple use cases that we’ve run across.

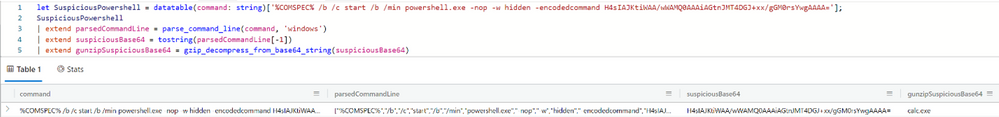

Decoding a suspicious PowerShell command

Sample suspicious PowerShell command decoded via KQL.

The suspicious command referenced here contains a value that is Gzip compressed and Base64 encoded. Here we’re using the built-in function parse_command_line() and gzip_decompress_from_base64_string() to get the plaintext.

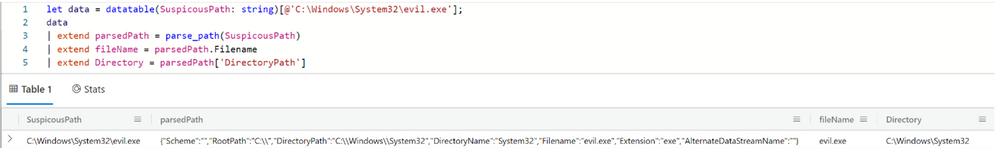

Parsing a file path using parse_path()

Sample of parse_path function usage and resulting output.

Notice how in this example we’re able to use parse_path() which returns a dynamic object of the various path components (Scheme, RootPath, DirectoryPath, etc) that can then be queried using either bracket or dot notation.

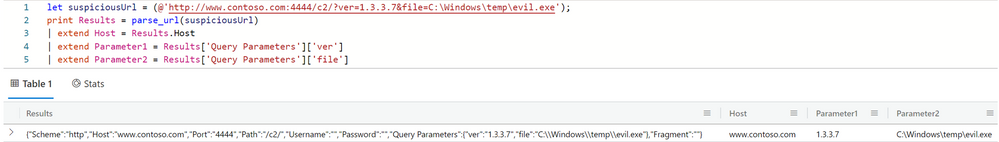

Parsing a suspicious URL using parse_url()

Sample of parse_url function usage and resulting output.

Here we use parse_url() in order to break down the URL into its various components. The result is a dynamic object that (similar to parse_path() example above), can be queried via bracket or dot notation.

Custom Functions

Along with the previously mentioned built-in functions, custom functions can also be created. This allows for the ability to write a query and save it for re-use without having to re-write the query again. Some examples of these can be found on Github for Microsoft 365 Defender Advanced Hunting.

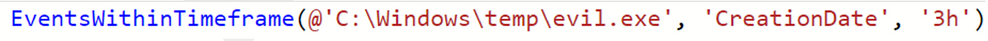

Custom functions go beyond only being able to surface artifacts of interest. Functions can add context to an artifact. Take the example of a malicious file created on a system:

C:\Windows\temp\evil.exe

A function can be created to identify what else may have occurred within a set timeframe around the creation of that file. Depending on the data that is collected, this can include other file creations, modifications, event log entries, and more.

The custom function called EventsWithinTimeframe() accepts 3 parameters:

- Filepath – in this case, our example from earlier “C:\Windows\temp\evil.exe”

- Timestamp type – for this example we’re focusing on the creation date

- Window of time – using 3h to indicate 3-hour time window before or after the creation date

The underlying query of the function takes the CreationDate of the artifact (C:\Windows\temp\evil.exe) and returns all relevant events (event log entries, other file creation events, etc.) that surround the creation time of the artifact +/- 3 hours. Of course, the data you collect may be different and the underlying query will differentiate based on the schema of the data, however, the logic for this example is something that can be implemented to suit your requirements.

Custom functions are limited only by your imagination. These can be simple one-line queries that help surface a particular artifact, a “utility” type function that converts data to a different format, or a more advanced type query that can provide a full context around a given artifact. You can even invoke functions within functions. Thanks to the power and flexibility of KQL the possibilities are endless.

Joining and External Data

Just like other query languages, KQL can perform a variety of joins. Kusto extends this capability beyond the current database to cross-cluster joins and even allows for external data sources to be queried and referenced. While joining is commonly done when enriching the context of current artifacts of interest (e.g., to another database that contains information about threat actor C2 infrastructure), let’s focus on the external data sources to show how this can be leveraged during incident response engagements, as well.

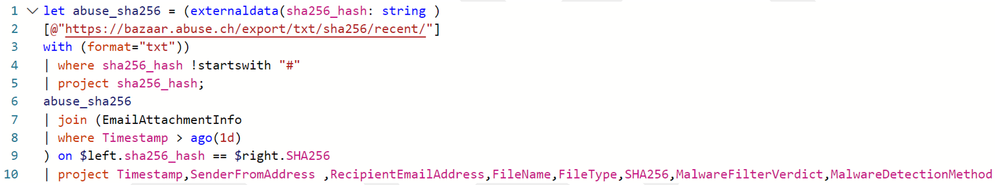

Using externaldata() to reference SHA256 hashes

Sample query using externaldata operator

This example is taken from a query shared on Microsoft 365 Defender Hunting Queries that checks for SHA256 hashes in an external feed against the SHA256 hashes from mail flow data. What’s great about this is that there is minimal setup to get the external data made useful for enriching the data being analyzed. You can work with a variety of file formats (CSV, JSON, TXT, etc.) and extract the data you need for working with it further.

Going even further with KQL

Beyond the functions that are built-in which help during an incident response investigation, KQL allows for even more capability and flexibility by being able to extend its usage with plugins. Incident responders will appreciate the R and Python plugins that Kusto offers to work with data beyond what is possible in native KQL today.

Both plugins allow for working with tabular input and will produce tabular output that can be worked with in any follow-on KQL. For the example below, we’ll be focusing on Python.

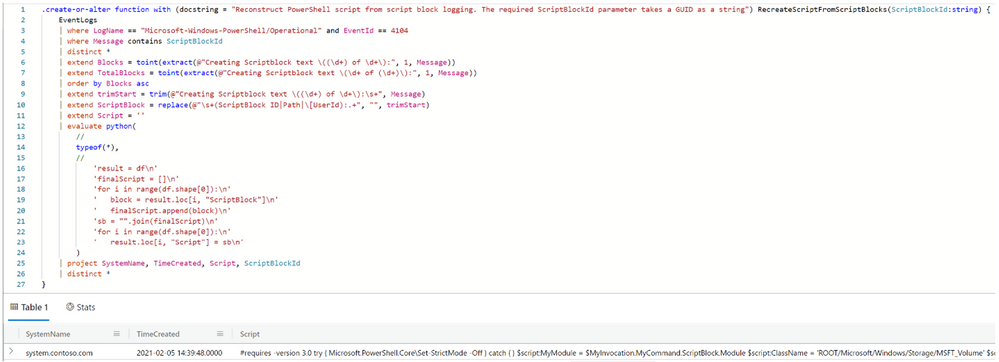

Recreating PowerShell Script from Event Logs

In certain cases, the only remaining artifact that gives the executed PowerShell comes from the PowerShell Operational Event ID 4104 entries, otherwise known as script block logging. In certain cases, the entirety of the PowerShell script is divided into multiple script blocks which must then be merged back together to view the full script. We’ll be using Python to accomplish this.

Lines 1 and 27 are the actual creation of the function. Lines 2 through 10 are used to query our collected data and prepare it for working with Python. Line 11 sets up the output column for our Python script. Line 12 uses the evaluate operator in order to invoke the Python plugin. Lines 13 through 24 are the actual Python that we use to work with the data as a Pandas dataframe. Note that Pandas and numpy are imported by default and other supported Python libraries can be imported as needed.

Conclusion

KQL allows for speed and flexibility when working with large datasets during incident response engagements. The built-in functions that are used to parse various pieces of data allow for analysts to work with what matters to them, rather than spending additional time trying to manually parse and process data. Custom functions provide users a method for taking a query and turning it into a sharable and repeatable action. KQL is further leveraged by enabling users to use scripting languages, such as R and Python, as another way to work with data.

Combined, these attributes and functionality, make KQL a highly effective tool for incident responders.

This blog and its contents are subject to the Microsoft Terms of Use. All code and scripts are subject to the applicable terms on Microsoft’s GitHub Repository (e.g., the MIT License).

Posted at https://sl.advdat.com/3mXKt53